by Tom Kuster, CMI Executive Director

From time to time in history, advancements in technology have made possible the emergence of a new art form. We are seeing that again with VR. History has shown us what to expect as the new art form is born, develops and matures. Some time passes and much experimentation takes place before the new art form finds its unique strengths and carves out its place in the stream of civilization.

Typically an art form’s early development simply imitates the art from which it emerged. In the first movies, the camera was simply pointed at a stage to record what was being done there. It took a while before Eisenstein, by exploring the power of filmic montage, and Welles, by demonstrating the effect of a moving camera, and a host of other film theorists and practitioners separated film from stage, and propelled film art on its separate and unique trajectory. Television, too, took a while to emerge from merely “visual radio” to find its own unique strengths – those different, too, from the strengths of film or those of the stage. Virtual reality, in its current early stages, will doubtless mimic television at first, as it is doing with the New York Times 360-degree productions that put the viewer right in the middle of a news story – you can turn around and see the refugee stream behind you and then look up to see the planes dropping supplies, and it’s like you are really there. Similarly, a virtual visit via Google Earth to Florence, of which I wrote in my previous post, feels a lot like a souped-up Rick Steves TV documentary. But there is more potential here. What will turn out to be VR’s real, essential, unique strengths as an art form, when will they be found, and who will find them?

Typically an art form’s early development simply imitates the art from which it emerged. In the first movies, the camera was simply pointed at a stage to record what was being done there. It took a while before Eisenstein, by exploring the power of filmic montage, and Welles, by demonstrating the effect of a moving camera, and a host of other film theorists and practitioners separated film from stage, and propelled film art on its separate and unique trajectory. Television, too, took a while to emerge from merely “visual radio” to find its own unique strengths – those different, too, from the strengths of film or those of the stage. Virtual reality, in its current early stages, will doubtless mimic television at first, as it is doing with the New York Times 360-degree productions that put the viewer right in the middle of a news story – you can turn around and see the refugee stream behind you and then look up to see the planes dropping supplies, and it’s like you are really there. Similarly, a virtual visit via Google Earth to Florence, of which I wrote in my previous post, feels a lot like a souped-up Rick Steves TV documentary. But there is more potential here. What will turn out to be VR’s real, essential, unique strengths as an art form, when will they be found, and who will find them?

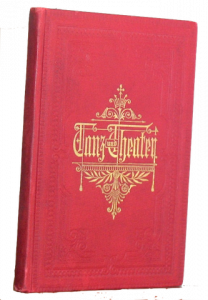

A similar developmental arc traces how a new art form becomes a medium for Christian messages. With the exception of the printing press, where the very first major product was the Gutenberg Bible, and where Luther harnessed its power to propel the Reformation, Christians have been slow to yoke the power of an art form in service of the gospel. In my personal library is a copy of C. F. W. Walther’s warning to Christians to avoid the theatre at all costs (Tanz und Theaterbesuch: Je zwei freie vorträge hierüber – Dance and theater attendance: Two free lectures on each of them, 1886). You can read in the 2016 GOWM online conference what today’s Lutheran artists say about the difficulties they still face promoting “church art.” While great Christian hymnody has adorned worship life since the Reformation, Christian popular music has lagged far behind. “Contemporary Christian music” has been notoriously second-rate both musically and doctrinally for many years, although some recent artists are finally achieving a measure of musical (if not doctrinal) excellence. To my ears the work Terry Schultz has done in Spanish signals we may at last be arriving both musically and doctrinally. But it has taken a while.

A similar developmental arc traces how a new art form becomes a medium for Christian messages. With the exception of the printing press, where the very first major product was the Gutenberg Bible, and where Luther harnessed its power to propel the Reformation, Christians have been slow to yoke the power of an art form in service of the gospel. In my personal library is a copy of C. F. W. Walther’s warning to Christians to avoid the theatre at all costs (Tanz und Theaterbesuch: Je zwei freie vorträge hierüber – Dance and theater attendance: Two free lectures on each of them, 1886). You can read in the 2016 GOWM online conference what today’s Lutheran artists say about the difficulties they still face promoting “church art.” While great Christian hymnody has adorned worship life since the Reformation, Christian popular music has lagged far behind. “Contemporary Christian music” has been notoriously second-rate both musically and doctrinally for many years, although some recent artists are finally achieving a measure of musical (if not doctrinal) excellence. To my ears the work Terry Schultz has done in Spanish signals we may at last be arriving both musically and doctrinally. But it has taken a while.

In film, after years of letting “Christian films” made by others promote decision and prosperity theology, the WELS films directed by Steve Beottcher (from Road to Emmaus, 2010,

to the upcoming To the Ends of the Earth, fall 2018) are finally bringing to the screen clear gospel messages with the professional quality the message deserves.

If history repeats itself, virtual reality as an art form will at first be exploited by the forces of irrelevance, or even of darkness – mere entertainment, or even pornography. But we know what it would take for us Christians – this time, for once – to influence and harness a new art form from its infancy. We know how we can jump in now, what to do with it and even how much it would cost.

Will we?